Transcript of Slow Burn: Season 1, Episode 7.

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of Episode 7.

View TranscriptRecently in Slow Burn

- Slow Burn Season 3, Episode 1: Against the World

- Slow Burn Season 3, Episode 7: To Live and Die in L.A.

- Slow Burn Season 3, Episode 8: Dead Wrong

- Slow Burn Season 3, Episode 2: Cops On My Tail

In May 1973, Elliot Richardson was poised to become Richard Nixon’s new attorney general. He didn’t know yet, but he would be out of the job in less than six months. During his confirmation hearings, Republican and Democratic senators alike demanded that Richardson appoint an independent special prosecutor to investigate the Watergate affair.

Reporter: … reports that no more hearings will be held until Richardson names a special prosecutor, with guidelines guaranteeing his independence.

Richardson promised that he would.

Now, if you were going to appoint a special prosecutor—someone to dig into a controversial, high-stakes, intrinsically political situation—you’d probably look for someone with a reputation for being nonpartisan. Someone without strong political ties. Someone it would be difficult to dismiss as biased.

Archibald Cox was none of those things. Which makes it really hard to understand why Richardson picked him.

Reporter:Archibald Cox: a big, blunt, crew-cut Harvard Law School professor, a liberal Democrat.

First off, Cox was like a cartoon of everything that Nixon and his biggest supporters hated: He was an elitist East Coast intellectual who wore bow ties and tweed suits. Even worse, he had worked for John F. Kennedy in the 1960 campaign against Nixon! When he was sworn in as special prosecutor, Cox invited Ted Kennedy—literally Nixon’s worst enemy—to attend as a guest.

AdvertisementNixon was not happy about Elliot Richardson’s choice. In his memoir, he would later write that if the attorney general had set out specifically to find the man that he, Nixon, would have trusted least, he couldn’t have done better than Archibald Cox. Nixon also described Cox as “a parasite” and “a partisan viper.”

Advertisement Advertisement AdvertisementReporter: Cox has been given extraordinary power to investigate the Watergate scandal. But that was the price Richardson had to pay for his confirmation as attorney general.

It’s baffling, in retrospect, that Richardson appointed a man who could so easily be accused of being out to get the president. But what’s even more baffling is that Nixon and his people didn’t even try to paint Cox as a liberal on a partisan witch hunt. As much as Nixon hated Cox, he made no public effort to discredit him.

AdvertisementThe White House certainly tried to stymie Cox behind the scenes—by ignoring or slow-walking his requests for documents, for example. And Cox, in turn, was wary of the White House, too. Having heard all about the Nixon team’s dirty tricks, he made sure that his headquarters could not be broken into by installing an elaborate security system with burglar alarms, television monitors, and motion detectors.

And yet, the team of young prosecutors who came to work for Cox never had the sense that their investigation was in any real danger. This was true even after the White House refused to obey a subpoena from Cox’s office in July, ordering Nixon to hand over the secret White House tapes whose existence had just been revealed to the Senate Watergate Committee.

Advertisement AdvertisementCarl Feldbaum: Pretty unanimously, we did not have a sense that there would be anything like a Saturday Night Massacre. Until the final week, when the stakes got very high.

That’s Carl Feldbaum. He was one of roughly 40 lawyers that Cox hired after he was appointed. Like most of the others, Feldbaum was a young Ivy League–educated liberal—he was just 30 years old and working as an assistant DA in Philadelphia when Cox brought him on.

AdvertisementAdvertisementFeldbaum:Many of us—the younger ones who eventually did get hired—were counseled not to take the job by older lawyers, more experienced. As in, what? You’re going to investigate the President of the United States? This president? Your career will be ruined. You’ll not get a job in any law firm, or you’re just going to destroy your career.

The young men and women of the Watergate Special Prosecution Force became friends. They hung out together after work. They ate meals together. They talked over drinks about the interviews they were conducting and the documents they were collecting. For most of that summer and fall, Archibald Cox and his prosecutors were fighting the Nixon administration in court for access to the White House tapes. The prosecutors wanted nine of them in particular—these nine recordings had been handpicked based on testimony from John Dean and others that suggested that they would have important conversations on them.

Advertisement AdvertisementFirst, a district judge ruled that Nixon had to obey Cox’s subpoena. Then a court of appeals upheld the decision.

Reporter: The court ruled that the president must turn his disputed secret tapes over to see if they have evidence of criminal acts.

But Nixon still refused.

AdvertisementFeldbaum: It was clear that Nixon had either decided on his own—or counseled with enough people—that the tapes would be truly damaging and had decided that it would be a mistake to hand them over and that he would do anything in his power to keep that from happening.

Leon Neyfakh: Right, including firing Cox.

Feldbaum:That’s right. But that final move did not occur to us until that last week.

It was Saturday, Oct. 20, when Richard Nixon gave the order to fire the special prosecutor who was investigating him.

AdvertisementAdvertisementReporter 1:The Tonight Showwill not be seen tonight so that we may bring you the following NBC News special report.

Reporter 2:Good evening, the president has fired special Watergate prosecutor Archibald Cox.

It was an order that also resulted in the abrupt departure of Nixon’s attorney general—Elliot Richardson—and Richardson’s second in command.

AdvertisementReporter 2: … saying he cannot carry out Mr. Nixon’s instructions. And the Justice Department is now headed, at the president’s direction, by the solicitor general, Robert H. Bork.

Within 24 hours, the cascade of dramatic exits at the Department of Justice became known as the Saturday Night Massacre.

But before Nixon made that final move, he tried to propose a compromise. Or at least, he tried to look like he was proposing a compromise. In reality it was more like a trick, one that would backfire on him in spectacular fashion and set up the final act of his ruined presidency.

AdvertisementOn today’s episode: What did Richard Nixon do when he felt the walls closing in? How did the country respond?

And what did it feel like for the young prosecutors investigating Watergate when they finally got to hear those tapes?

This is Slow Burn. I’m your host, Leon Neyfakh.

Advertisement AdvertisementReporter 1:The news caused a sensation in the White House press room and sent reporters scrambling for their telephones.

Carl Feldbaum: The FBI agents were under orders to seal the office, as though it was a crime scene.

Reporter 2: In my career as a correspondent, I never thought I’d be announcing these things.

Episode 7: Saturday Night

When the court of appeals ruled against Nixon in the tapes case on Oct. 12, the president was left with two options: He could either give Cox the nine tapes he had requested, or he could take his chances with the Supreme Court. The deadline for making the decision was midnight on Friday, Oct. 19.

Advertisement AdvertisementReporter:Today was the deadline for the president to appeal to the Supreme Court, but for a reason as yet unexplained, the president’s men have not filed the appeal.

After some fitful scrambling, Nixon and his team of lawyers decided on a third way.

Here’s what they came up with: Instead of giving Archibald Cox the tapes, Nixon and his people would write up summaries of what was on them. Then the president would let a neutral third party listen to the tapes and verify that the summaries were accurate and didn’t leave anything important out. The idea was that Cox, and the entire nation, would trust this neutral third party when he declared that Richard Nixon was on the level.

AdvertisementSo, who should be the neutral third party? The Nixon administration had someone in mind: a Democratic senator from Mississippi named John C. Stennis.

AdvertisementStennis was about as surprising a choice for “neutral third party” as Archibald Cox was for “unassailably nonpartisan special prosecutor.” First off, he was a staunch Nixon supporter—a Democrat, but a Southern Democrat who had backed the president on many of his policy initiatives.

But the other thing about Stennis was that he was famously hard of hearing.

Phil Lacovara: When we heard that so-called compromise, the reaction was astonishment.

That’s Phil Lacovara. He was counsel to Archibald Cox.

Lacovara:It immediately struck us as being a kind of con job.

It was more of a con job than they even realized. As the world would learn only later, it would have been hard for someone with perfect hearing to make out anything Nixon and his aides were saying on these tapes. Nixon had chosen to use a cheap, janky taping system, and it made extremely low-quality recordings.

Advertisement AdvertisementThe idea of a partially deaf 72-year-old, alone in a room, listening to these tapes and comparing what he heard to a written summary prepared by Richard Nixon? It was like the punchline to a joke.

Did I mention Stennis had just gotten out of the hospital? Less than a year earlier, he had been mugged outside his house and shot in the chest. He was basically fine—he would live another 20 years after this. But, you know, still: not the guy you’d pick to assure everyone that there was nothing incriminating on these tapes.

Here’s Lacovara again:

Advertisement AdvertisementAdvertisementLacovara:I can’t say that they deliberately chose somebody who was frail and elderly. I think the idea was this was going to be a politically attractive so-called compromise because they were asking a Democrat who was a senior member of the Senate to engage in this task and that might seem to have a kind of patina of plausibility behind it.

It got worse from there. By the time Nixon put his terms down on paper in a letter to his attorney general, he stipulated that after Cox got the summaries of the nine tapes he had already requested, that would be it. The special prosecutor’s office could not ask for any more memos or recordings from the White House. It would be a one-shot deal.

The so-called Stennis Compromise was a non-starter. Here’s Jim Doyle, a former political reporter who served as press secretary for the Watergate Special Prosecution Force.

Advertisement Advertisement AdvertisementJim Doyle:It was a very cynical choice. It wasn’t going to get by Archibald Cox. Any defense attorney for the most minor defendant would get up and say, “Your Honor, throw this case out unless we get the evidence.”

In multiple conversations with Elliot Richardson, the attorney general who had appointed him, Cox rejected Nixon’s proposal. He suspected that the White House was deliberately offering him terms that they knew he couldn’t accept. It seemed like they were setting up a conflict to justify firing him.

At 8:15 on Friday night, Cox’s suspicion was confirmed when Nixon went public with the Stennis Compromise.

Reporter:The president has offered a compromise designed to circumvent a court order which would have required him to turn over the secret tapes to a federal judge.

In a written statement, the president explained his idea and expressed his regret that Archibald Cox had turned it down.

Cox, who had already driven home for the night, returned to the special prosecutor’s office and dictated a statement to Jim Doyle, who called it in to the papers five minutes before the print deadline:

AdvertisementAdvertisement AdvertisementJim Doyle:This is Jim Doyle from Archibald Cox’s office. I have a statement that I’m gonna read as fast as you can take it. It’s from special prosecutor Archibald Cox: “The president is refusing to comply with the court decrees. Period. I shall bring these points to the attention of the court and abide by its decision.”

With that, Archibald Cox’s fate was sealed. But the game was not over. Cox still had one play left. He would take his case directly to the American people.

Reporter:Archibald Cox, the special Watergate prosecutor, is about to hold a press conference.

On the afternoon of Saturday, Oct. 20, 1973, cameras followed Archibald Cox and his wife Phyllis as they walked hand-in-hand to the front of a staging area at the National Press Club. Cox sat down alone at a table covered in a mustard yellow table cloth, with an American flag behind him. He began speaking, slowly and patiently, to the reporters who had gathered to hear him.

Advertisement AdvertisementArchibald Cox:I read in one of the newspapers this morning the headline, “Cox Defiant.” I do want to say that I don’t feel defiant. In fact, I told my wife this morning, I hate a fight.

Cox’s plan was to plainly lay out the constitutional issues at hand: to explain why he couldn’t compromise on the subpoena, and why it was so important that the president not be allowed to defy the Special Prosecution Force.

It was a bold move for this patrician Harvard professor—this card-carrying member of the liberal establishment. Hewas going to address Nixon’s silent majority, and somehow make them listen to reason?

Yeah, he was. And somehow, it worked.

Advertisement AdvertisementCox: As you all know, there has been, and is, evidence of serious wrongdoing on the part of high government officials.

Cox didn’t dumb down his analysis of the situation or pretend that it wasn’t complicated. He also made clear that he took no pleasure in what was happening.

Cox: It’s sort of embarrassing to be put in the position to say, “Well, I don’t want the president of the United States to tell me what to do.” I was brought up with the greatest respect for every president of the United States.

Jim Doyle stood off to the side and watched with admiration as the cameras rolled.

AdvertisementDoyle:It was in the middle of a Saturday afternoon—you know, football day in America. In fact, ABC didn’t carry the press conference live because they had too many commitments to college football. But he was live on NBC and CBS, and it was a masterstroke. And it was all Archie.

He spoke sincerely and carefully. Wearing a tweed jacket and reading glasses, he explained why the Stennis Compromise was not going to work.

AdvertisementCox:It’s not a question of Sen. Stennis’ integrity—I have no doubt at all of Sen. Stennis’ personal integrity. But it seems to me that it’s terribly important to adhere to the established institutions and not to accommodate it by some private arrangement involving, as I say, submitting the evidence ultimately to any one man.

After he had said his piece, Cox took questions from reporters.

Advertisement AdvertisementAdvertisementReporter:How could you expect to succeed in this job? How could you expect to succeed?

Cox:Well, I thought it was worth a try. I thought it was important. If it could be done, I thought it would help the country. And if I lost, what the hell?

Jim Doyle believes it was Cox’s performance during this historic press conference—the way he trusted the American people’s intellect and believed in their investment in civic life—that set the Watergate story on the path to its conclusion.

Doyle:It’s the press conference that, really, Richard Nixon did not survive.

Of course, neither did Cox.

Right after Cox’s press conference, Elliot Richardson got a call from Nixon’s chief of staff, Alexander Haig. Haig had been quarterbacking the White House response to the Cox subpoena. His message left no room for Richardson to negotiate: The president was ordering him to fire Archibald Cox.

Richardson had promised Congress that he’d preserve the special prosecutor’s independence.

Now he was being asked to terminate him for not going along with the White House’s demands. He did the only thing he thought he could do: He refused. At 4:30 that afternoon, Richardson came to see Nixon with a resignation letter in his pocket.

Now, to understand the conversation these two men proceeded to have, you have to know about something that has very little to do with Watergate.

AdvertisementReporter 1: Good evening. Here’s the latest on the Middle East war. The fighting is still going on …

Reporter 2: This particular battle pitted Israeli tanks against a pocket of Egyptian infantry, and the Egyptians fought hard … [sound of explosion]

The Yom Kippur War was sparked when a coalition, led by Egypt and Syria, launched a surprise attack on Israel during the first week of October.

The conflict almost immediately drew in the U.S. and the Soviet Union, and for a while it looked like there might be a military confrontation between the two superpowers in the Middle East.

AdvertisementUnderstandably, Nixon had the Middle East and the Soviet Union on his mind when his attorney general walked into the Oval Office that day. But the president did not waste a minute before trying to use the crisis to pressure Richardson to fire Cox instead of resigning. Here’s Richardson, who died in 1999, telling the story in a BBC documentary:

Advertisement Advertisement AdvertisementRichardson: He started talking about the Middle East, and he went on to say, “You realize that Brezhnev could make a very serious miscalculation in the light of what could happen as you go forward?” I said, “Mr. President, I don’t feel that I have any choice. I cannot do it.” And the president said, “Elliot, I’m sorry you choose to put your purely personal commitments ahead of the public interest.” And I could feel the blood rushing to my head, and I could’ve made a very angry response. But what I did say—in as level a voice as I could muster—I said, “Mr. President, it would appear that you and I have a different perception of the public interest.”

After Richardson’s resignation was accepted, the deputy attorney general, William Ruckelshaus, was next in line as head of the Justice Department. After consulting with his now-former boss, Ruckelshaus also resigned instead of firing Cox.

AdvertisementNext in the line of succession was the solicitor general, Robert Bork. Unlike Richardson, Bork had not made any promises to Congress about giving the special prosecutor independence. For this reason, Richardson advised Bork that he could and should carry out Nixon’s order with a clear conscience. Richardson worried that if Bork followed him out the door, the federal government would be dangerously destabilized.

Carl Feldbaum, the lawyer from Cox’s team, was at home while all this was taking place. He was having dinner with his wife Laura and two of his colleagues when he got a phone call informing him that Cox had been fired. Even worse: FBI agents were apparently headed to the special prosecutor’s office to take it over and seal it up on orders from the White House. Feldbaum and the others understood right away that they had to get there—fast.

AdvertisementAdvertisementFeldbaum:So, the four of us jumped in my car, drove downtown, down Massachusetts Avenue—must have taken us eight or 10 minutes, no more.

Feldbaum’s wife Laura parked the car while the three prosecutors raced upstairs to the office. They were determined to get their hands on the evidence that they’d gathered before the federal agents could seize it. They were relieved to find that they were the first ones there. Feldbaum went straight to his safe and started feverishly entering the combination.

Feldbaum:For the first time I was able to actually open that safe on my first try. At that point, my wife had walked into the office, and I thought it was the safest thing to give her the evidence, which she stuffed into her jeans. And just as she was headed out, the elevator doors opened, and the FBI agents came in.

That was when the chaos really started.

Advertisement AdvertisementReporter: Agents of the FBI, acting at the direction of the White House, sealed off the offices of the special prosecutor. That’s a stunning development, and nothing even remotely like it has happened in all of our history.

As word of the night’s events hit the news networks, more members of the Special Prosecution Force made their way to the office. What ensued was a standoff. On one side was Cox’s army; on the other was Nixon’s FBI.

Advertisement AdvertisementFeldbaum: They were under orders to seal the office, as though it was a crime scene. It was like, taping up desks and phones. And nothing would come in, nothing would go out.

When Jim Doyle, the press secretary, arrived, the building was at this point swarming with reporters. He advised the top-ranking member of the office, Cox’s now-former deputy, Hank Ruth, to hold a press conference. Doyle led the reporters upstairs to a dark, smoky room where the prosecutors kept their law books, and Ruth addressed the crowd.

AdvertisementHank Ruth: One thinks that in a democracy maybe this would not happen and that maybe we could proceed in good faith to prosecute those who have violated the criminal law. Apparently that is not to be the case.

Afterward, a reporter came up to Jim Doyle and asked him what he was going to do next.

Doyle: I said, “Well, I’m going home to read about the Reichstag Fire,” which of course is the famous fire which the Nazis used to say that they were under siege and to basically take over Germany.

Advertisement Advertisement AdvertisementReporter:All of this adds up to a totally unprecedented situation—a grave and profound crisis in which the president has set himself against his own attorney general and the Department of Justice …

As the hour crept toward midnight, the big question hanging in the air was whether the Watergate Special Prosecution Force had been merely decapitated, or fully shut down. Here’s Phil Lacovara, the counsel to Archibald Cox:

Lacovara:So, there was that initial confusion when we gathered. Where does the Watergate Special Prosecution Force stand? We know that Cox has been fired. What’s the status of the office? What’s the status of the investigation?

NBC News seemed certain that the office was done.

AdvertisementReporter:The president has abolished special Watergate prosecutor Cox’s office and duties and turned the prosecution of Watergate crimes over to the Justice Department. And what it means is that the worst dreams of everyone who is worried about the president’s secret tapes have now become true.

But the staff of the Special Prosecution Force weren’t so sure that they were through. As they discussed that night amongst themselves, none of them had actually been fired. No one had told them, in writing or otherwise, that they should stop doing what they were doing.

Advertisement AdvertisementFeldbaum:It was a little unclear—the language was unclear—as to whether the staff and the office was abolished. There was some uncertainty about that, and we decided to decide the uncertainty in our favor and not get fired.

For days after the Saturday Night Massacre, the team of prosecutors gathered at a house where one of them lived. They ate take-out, they drank, and they talked about their options.

AdvertisementSome of the younger prosecutors wanted to present the White House with a list of conditions and threaten to resign en masse if they weren’t met. Jim Doyle hated that idea. He remembers saying, “That’s exactly what they want us to do—posture like rampaging college kids. … If they’re going to fix these cases, they should have to do it over our prone bodies.”

AdvertisementBut for all of Doyle’s bluster, most members of the staff were preparing themselves for the worst, and what felt like the inevitable: that their team would be disbanded, and their work would, at best, be handed over to a Nixon yes-man in the Justice Department. It seemed obvious—if Nixon wasn’t going to get rid of them, what had been the point of firing Cox?

AdvertisementOne theory was that Nixon was counting on the prosecutors to resign in protest after Cox was fired, and that when they stayed put, he didn’t know how to justify getting rid of them. If that’s true, it would be one of two major miscalculations that Nixon and his team made before the Saturday Night Massacre. The other was thinking that the public wouldn’t really care that he had fired Archibald Cox.

AdvertisementThe Stennis Compromise, Nixon thought, sounded like a reasonable proposal—one that Americans would appreciate and understand. Nixon was trying to accommodate the subpoena, and Cox had turned him down, so he had to go.

The reaction Nixon got was not the reaction he had been expecting.

AdvertisementReporter:Not since Harry Truman fired Gen. MacArthur has there been such an outraged public reaction. New opinion polls and the outpouring of telegrams and phone calls flooding in on Congress now raise the question whether Mr. Nixon can ride this one out …

A Gallup poll found that just before the Saturday Night Massacre, 31 percent of respondents approved of Nixon’s performance in office. Immediately afterward, it dropped to an extraordinary 17 percent.

Advertisement AdvertisementDoyle: There was a sense that some kind of national government coup was going on.

Neyfakh: Were people scared?

Doyle: I think at that point people were very scared. I think that was the first time that they had seen this kind of assault on the government as an entity.

Right away, the fear began to mix with anger. On Sunday morning, a man wearing a Nixon mask and prison stripes took up a position on Pennsylvania Avenue holding a sign that said, “Honk For Impeachment.” As Doyle remembers it, the honking didn’t stop for two weeks. It came from cars, trucks, tour buses—even police cars.

Advertisement AdvertisementReporter: Western Union said that the firing of Archibald Cox produced a record number of telegrams to its Washington offices.

So many people sent telegrams to Washington that weekend that Western Union was completely overwhelmed and had to set up special high-speed printers and call in extra workers from outside the city.

Richard Nixon later said that the White House staff was “taken by surprise by the ferocious intensity of the reaction,” and by how “badly frayed the nerves of the American public had become.”

Reporter:More than 50,000 telegrams poured in on Capitol Hill today. Most of them demanded impeaching Mr. Nixon.

Unidentified: These come from Republicans, and businessmen, and people—most of whom begin their statement by saying, “I’ve supported the president, I’ve never believed in impeachment, but he’s now gone too far, and we want the Congress to take strong action.”

Members of Congress too began to ring the alarms, and for the first time since the Watergate break-in, powerful people in Washington, D.C.—including Republican members of the House—began to talk seriously about impeachment.

AdvertisementReporter:The speaker of the House, Carl Albert, is expected to ask the Judiciary Committee to begin an inquiry on impeachment Wednesday …

On Tuesday, Oct. 23, Nixon’s lawyers were set to appear in court. Their initial plan was to argue before a judge that he should accept the Stennis Compromise and rule that the written summaries Nixon had offered would properly satisfy the still-unresolved subpoena.

AdvertisementBut by Tuesday, it was clear that firing Cox had been a massive political mistake, and the Stennis Compromise was dead in the water. After a meeting of top aides that one of them later described as “painful and anguishing,” it was decided that the president’s lawyer, Charles Alan Wright, would not be bringing up the compromise in court. With about a dozen lawyers from the Special Prosecution Force seated across from him in the courtroom, Wright instead told the judge that the president would comply in all respects with the subpoena. “This president does not defy the law,” he said.

Jim Doyle remembers the moment well.

Doyle:It was an enormous victory for the courts. And it was an enormous victory for Cox, who had mounted this appellate court case.

Three days after this surprise capitulation, on Oct. 26, Nixon gave his first press conference since the Saturday Night Massacre.

Advertisement AdvertisementNixon:Would you be seated, please. Ladies and gentlemen, before going to your questions, I have a statement with regard to the Mideast …

He began by addressing the still-simmering standoff in the Middle East, calling it “the most difficult” situation the country had faced since the Cuban Missile Crisis. He also justified his decision to fire Archibald Cox.

Nixon: We find that these are matters that can be worked out and should be worked out in cooperation and not by having a suit filed by a special prosecutor within the executive branch against the president of the United States.

His defensive posture notwithstanding, Nixon assured reporters that arrangements for the handover of the tapes were underway. He also announced that the special prosecutor’s office would not be disbanded after all. Instead, the acting attorney general would soon appoint someone new to oversee the investigation. The gambit by Jim Doyle and the others had worked!

AdvertisementAbout halfway through the press conference, a reporter reminded Nixon that, before he was elected, he had once said that “too many shocks can drain a nation of its energy.” Did the president think America was at that point now?

Nixon replied with what might be the least convincing display of presidential swagger ever seen.

AdvertisementNixon:Uh, I have never heard or seen such outrageous, vicious, distorted reporting in 27 years of public life. When people are pounded night after night with that kind of frantic, hysterical reporting, it naturally shakes their confidence. And yet, I should point out that even in this week, the president acted decisively in the interests of peace and the interest of the country. These shocks will not affect me in my doing my job.

Carl Feldbaum remembers watching the press conference on television at a colleague’s house. As he listened to the president speak, he felt scared.

Feldbaum: He appeared unhinged to us, and Hank Ruth worried that the pressures of the investigation and everything else that was going on was making him unstable.

Neyfakh: Gosh, I mean, were you just imagining him hitting the button, so to speak?

Feldbaum:Well that was the most dire, of course. But imagining some major foreign policy, war-like deflection of events that we must have the president now. This cannot be interrupted. We need a commander in chief of our armed forces. That was clearly not just a concern—a deep worry.

On Nov. 1—11 days after the Saturday Night Massacre—Feldbaum, Doyle, Lacovara, and the rest of the Special Prosecution Force learned the identity of their new boss.

AdvertisementReporter: Good evening. The new special Watergate prosecutor arrived in Washington today. Leon Jaworski is the new man: a 68-year-old conservative Democrat from Texas.

Robert Bork, the same Justice Department official who had fired Archibald Cox, had now appointed a lawyer named Leon Jaworski to replace him.

The prosecutors were reflectively skeptical of Jaworski.

Advertisement AdvertisementFeldbaum: He was an establishment lawyer to us and had great respect for the presidency and, reportedly, respect for the president. I guess it is fair to say that we young staff members were suspicious.

About a month later, Feldbaum remembers sitting with Jaworski in the office when the phone rang. It was one of Nixon’s lawyers, Fred Buzhardt, and he had a message: The first batch of tapes were ready to be picked up at the White House.

Feldbaum volunteered to walk over, not thinking about the fact that it was a Saturday, and he was dressed for the weekend in pink bellbottoms. He remembers making his way through the crowds and into the White House, showing his credentials, and entering Fred Buzhardt’s office. There, on a round table in the middle of the room, Feldbaum saw the tapes.

AdvertisementFeldbaum: These are big reels of tape, and they were labeled, but they were, I would say, naked—just lying there. They didn’t seem to be protected in any way. Just sitting on a round table in his office. And I asked for something to take them back with.

Neyfakh: [Laughs] Like a bag?

Feldbaum:A bag or a box. I eventually got a cardboard—a small cardboard box.

Sheepishly, Feldbaum asked for a receipt, and Buzhardt wrote one out on a scrap of paper.

AdvertisementFeldbaum:And we both signed it, and I folded it up, put it in my pocket, and walked out of his office and out of the White House, through the throng of tourists and the four or five blocks—right, you know, down city streets, through the Capitol—to our offices.

When Feldbaum got back to the office, he and three other prosecutors gathered around a reel-to-reel player. Feldbaum asked which tape they should play first, and someone suggested March 21, 1973. It was one of the conversations that John Dean had described in his testimony as being particularly damning to the president.

Feldbaum:We got out that tape, strapped on headphones, and I put the reel in and was careful to tape down the Record button, so there was no chance that we would erase any part of the tape.

The four of them sat there and listened for about seven minutes. Then they heard it.

It was just like Dean had said in his testimony: He had told the president that keeping the Watergate burglars quiet would cost a million dollars over two years.

Advertisement AdvertisementDean:I would say these people are going to cost a million dollars over the next two years.

And the president had said he could get that much—and he could get it in cash.

Nixon: You could get a million dollars. And you could get it in cash.

Feldbaum:And we just took off our headphones at that point, looked at each other, and understood that that was a federal crime: obstruction of justice. And we sort of looked at each other for a moment, and I don’t know that we even spoke, and I just said, “We need to take this in and let Leon listen to it.”

Leon Jaworski was in his office. Feldbaum told him he needed to see him. Then he handed him a headset.

AdvertisementFeldbaum: And I said, you know, we had just listened to this part of the tape, and I teed it up and turned on the tape. And Leon Jaworski stared straight at me, listening to those first five or seven minutes of the tape, and when we got to that point and to the president’s response, I waited for orders from Leon Jaworski, and he said, “Thank you.” He just stared at me. It was one of the—it was the greatest poker face I had ever seen.

Slow Burn is a production of Slate Plus. If you like Slow Burn, do us a favor and leave us a rating and a review on iTunes. It really helps new listeners find the show. Also, tell your friends. You can direct them to applepodcasts.com/slowburn.

Slate Plus members get a complete bonus episode of Slow Burn every week, going deeper into the wild world of Watergate. I’m sharing some of the amazing stuff I’ve found while doing my research and playing extra interviews with people who watched it all go down. This week, I’ve got an interview with the one and only John Dean, former White House counsel to Richard Nixon. If you’ve been listening to the show, you know that Dean helped plan the Watergate cover-up before blowing it up on national television. The subject of our discussion is the mysterious 18-and-a-half–minute gap on one of the key White House tapes that Nixon was supposed to turn over to the special prosecutor’s office.

Slate Plus members help support this show and the rest of our work.

Slow Burn is produced by me and Andrew Parsons. Our script editor is Josh Levin. Gabriel Roth is the editorial director of Slate Plus. The artwork for Slow Burn is by Teddy Blanks from Chips. Thanks to the NBC News archives, the BBC, and the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum for the archival audio you heard in this episode.

Thanks to Slate’s Chau Tu, Rachel Withers, June Thomas, and Steve Lickteig. You can find a full list of books, articles, and documentaries used to research this episode on our show page.

Tweet Share Share Comment相关文章

高燃!哨响表停赛不止,2024广东“村BA”开赛在即,一分钟带你重温高光瞬间。

2024-09-21 本报讯近日,名山区人民检察院与四川通用航空投资管理有限责任公司检企合作签约仪式举行。双方签署《“检企共建法治护航”检企合作协议》以下简称:《协议》),积极探索检察机关与企业合作的新思路、新模式和新做法2024-09-21

本报讯近日,名山区人民检察院与四川通用航空投资管理有限责任公司检企合作签约仪式举行。双方签署《“检企共建法治护航”检企合作协议》以下简称:《协议》),积极探索检察机关与企业合作的新思路、新模式和新做法2024-09-21 位于青岛台东万达广场二层、三层的利群商厦万达店25日正式开业,其中,二楼主营精品生活超市、餐饮,三楼为精品运动品牌及婴童城。新店总面积2万多平方米,通过连廊与利群商厦相贯通。据利群商厦总经理纪淑珍介绍2024-09-21

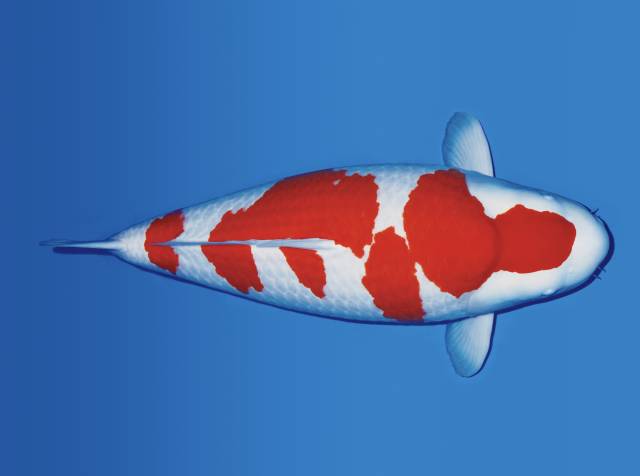

位于青岛台东万达广场二层、三层的利群商厦万达店25日正式开业,其中,二楼主营精品生活超市、餐饮,三楼为精品运动品牌及婴童城。新店总面积2万多平方米,通过连廊与利群商厦相贯通。据利群商厦总经理纪淑珍介绍2024-09-21 揭秘!看“百万”锦鲤如何游进水产种博会_南方+_南方plus“氧气包准备好没?”“注意水温不要太低。”“搬运过程中切记轻拿轻放。”……图为红白锦鲤。受访者供图11月24-26日,第四届中国水产种业博览2024-09-21

揭秘!看“百万”锦鲤如何游进水产种博会_南方+_南方plus“氧气包准备好没?”“注意水温不要太低。”“搬运过程中切记轻拿轻放。”……图为红白锦鲤。受访者供图11月24-26日,第四届中国水产种业博览2024-09-21

[Herald Review] Tori Kelly thrills fans, hints her love for Korean artists

Tori Kelly performs during her first concert in Korea held at Seoul, Tuesday. (Live Nation Korea)Ame2024-09-21 本报讯近年来,名山区红星镇通过实施“两项改革”,优化资源配置、提升发展质量、增强服务能力、提高治理效能,把改革成果转化为发展红利和治理实效,促进乡村振兴发展。红星镇党委借改革之机加强村级班子建设,坚持2024-09-21

本报讯近年来,名山区红星镇通过实施“两项改革”,优化资源配置、提升发展质量、增强服务能力、提高治理效能,把改革成果转化为发展红利和治理实效,促进乡村振兴发展。红星镇党委借改革之机加强村级班子建设,坚持2024-09-21

最新评论